Simpler, cheaper and serving non-consumers, disruption creeps in from the edges

To get a glimpse of what’s ahead for health care — both the medical industry and the consumer services that will grow up, around and below that industry — there’s no better guide than the theory of innovation and industrial life cycles first described in 1995 by Clayton Christensen, a professor at Harvard Business School.

Here’s my summary disruptive innovation, based on multiple readings Christensen and his acolytes.

First, the scene is set.

- chasing profits, a mature industry focuses on its most lucrative customers, building what Christensen calls “sustaining innovations”

- coddling those high-end customers, the mature industry often relies on an expensive sales/marketing infrastructure (salespeople, showrooms, magazine ads, conference sponsorships, consultant’s fees)

- eventually, the goods or services on offer exceed the needs and price point of many customers — some know they’d settle for a lower quality product/service, particularly if it’s significantly cheaper and serves some previously unserved need

- frustrated customers who can’t afford these over-engineered solutions start to hack solutions themselves using weaker, cheaper tools

- a non-incumbent producer, often from an adjacent industry, starts selling a low-end product, often through a new, cheaper sales/marketing channel

- the non-incumbent market entrant steadily innovates on both the product and the business model

Now the big action comes… disruption!

- lower prices unlock new demand from different, previously unforeseen customers, and an entirely new type of buyer emerges that’s far bigger than the original “elite” customer group.

- new features are created to serve that new customer group, providing benefits that were unimaginable or unachievable in the prior industrial matrix. (Lots of examples here.)

- the new product eventually improves enough on the original metric of success that it eventually exceeding the capacities of what’s needed by the original high-end customers.

- they desert. The industrial incumbents that have served the elite faithfully collapse.

Disruption complete.

(If you’re a biz geek, its also worth reviewing the first two minutes of this interview with Christensen.)

Arguably, we’ve already seen a blueprint for what’s ahead for the medical industry in the last 20 years as technology has, time and again, blown up previously dominant information processing incumbents. (And what is the medical industry, if not an information processing incumbent?)

Some examples of information processing incumbents that were rock solid 20 years ago but have subsequently been have been disrupted:

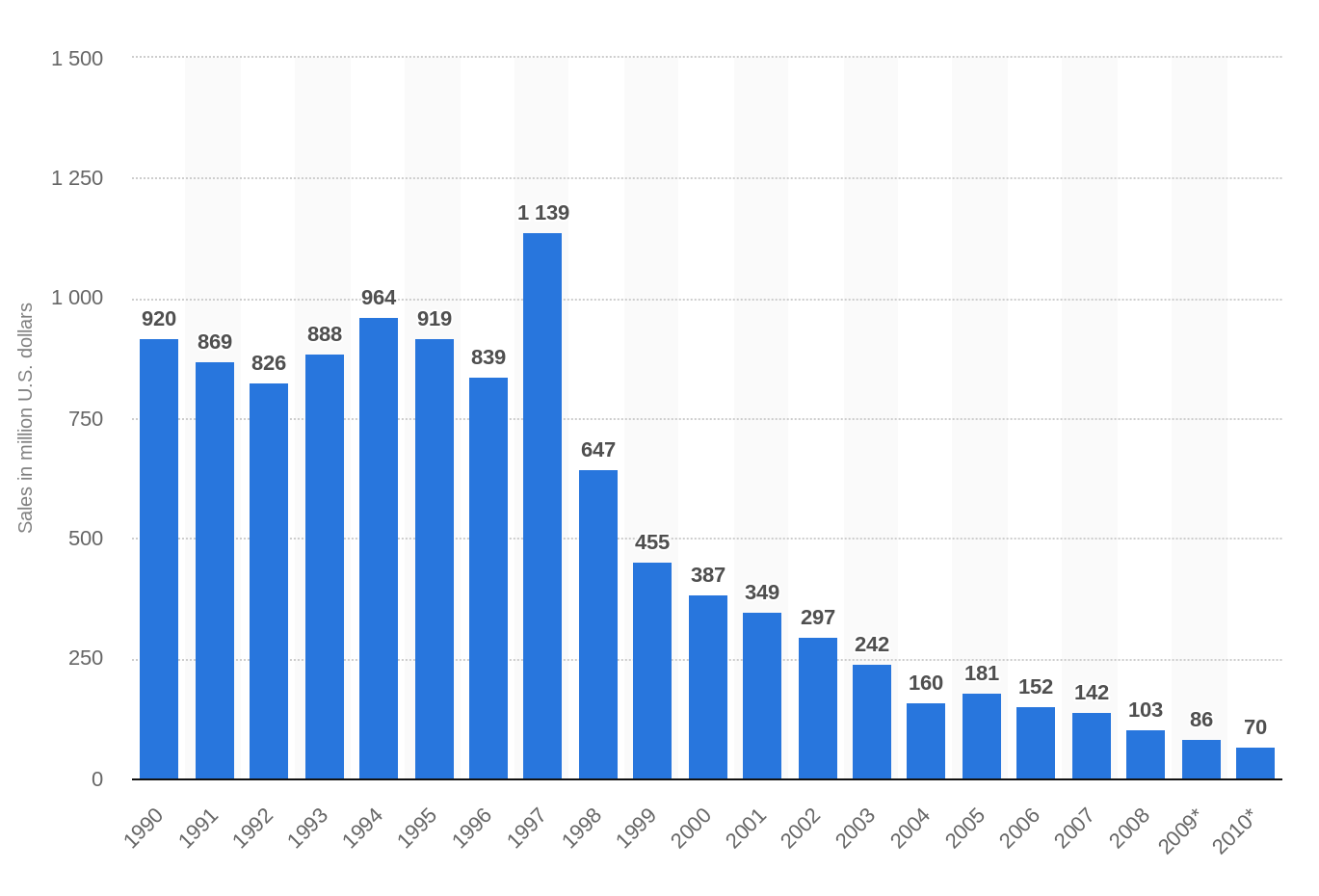

- Annual sales of the Encyclopedia Britannica dropped from 120,000 in 1993 to below 10,000 before print sales ceased entirely in 2012.

- The newspaper industry, which once employed 400,000 people in the US, has been eviscerate as consumers swap or create news on their own on Facebook.

- More recently, movie moguls have realized they can’t compete with the breadth and depth of Netflix, much less a witch’s brew of Fortnite, Pornhub and Joe Rogan’s Youtube channel.

- Fax machines. Say no more.

(But obviously that’s not exactly going to happen. Medicine is far more than a vast information processing machine — it’s a nurse’s careful touch, an ER doctor’s probing questions, an obstetrician’s forceps, an orthopedic surgeon’s meticulous drilling.)

In the medical industry, all these forces will work together to create massive and unforeseeable second order effects. Did anyone predict that flip phones would eventually lead to the Apple and Google App stores, with uncountable apps and generating $100 billion in annual revenue?

(It’s worth noting that, Christensen’s 2010 book applying his own theory of disruption to medicine, The Innovator’s Prescription, was tangled and uncompelling. Worse, it basically punted on the dream that the industry of medicine would be disrupted. Christensen concluded that though specialities like radiology might be disrupted, and nurses might someday be empowered by technology to do the work of specialists, the overall problem of medical gridlock might only be resolved by a mix of government intervention and luck. This may be a case of bad timing. Christensen hadn’t yet glimpsed many of the forces and technologies sketched in this essay. This isn’t the first time Christensen overlooked disruptive technology right before it took off. His 2013 book Innovator’s Solution pooh poohed the value of cameras in cell phones.)

Read next: Part 8: Ten possible frontiers of consumer-led healthcare change.

INDEX

Prologue: Two times Fitbit didn’t save my life; my six month journey on the borderlands of my own health data.

Part 1: My night continues downhill. Fitbit’s muteness gets louder.

Part 2: 23andme detects no clotting genes; demand for genetic expertise outpaces supply; DNA surprises about my personality and eating habits.

Part 3: A cartoon of the future of the medical industry.

Part 4: Five categories of predictable exponential tech change: devices, granularity, volume, utilization, software.

Part 5: Two categories of unpredictable change: the demands of individuals and their communities.

Part 6: Medicine, already trailing state-of-the-art techniques and technology by 17 years, gets lapped.

Part 7: Like fax machines, newspapers and encyclopedias, is medicine another information processing machine on the verge of being disintermediated by mutating consumer demands and tech innovation?

Part 8: Ten possible frontiers of consumer-led healthcare change.

Part 5: Two categories of unpredictable change: the demands of individuals and their communities.

Part 6: Medicine, already trailing state-of-the-art techniques and technology by 17 years, gets lapped.

Part 7: Like fax machines, newspapers and encyclopedias, is medicine another information processing machine on the verge of being disintermediated by mutating consumer demands and tech innovation?

Part 8: Ten possible frontiers of consumer-led healthcare change.