Safe at the ER… then my heart rate plummets

I obviously survived the morning run on October 6, though I walked most of the second half of my four mile “run.”

After lunch, I talked with my kids about what I described as my “odd health development.” They suggested I go immediately to the emergency room. I shared my analysis of the cons of a too-hasty visit to the ER, without worrying them with my cancer self-diagnosis. Knowing that I’m ornery and contrary, they kept hinting and nudging, but didn’t try shoving me out the door or calling 911.

I coughed up blood a few more times as the day passed. Harboring my own grim self-diagnosis of cancer, I dismissed my kids’ Google-based (and in retrospect accurate) attempts at diagnosis. I made it through the daylight hours. Though I wasn’t thinking about this consciously, I regularly stood and paced, or jiggled my posture to dull the jabs.

But when I finally tried to lie down in bed at roughly 11.30pm, the jabs were sharp and unavoidable. Cancer or not, I realized that the only way I was going to sleep was by getting to the hospital. I drove 10 minutes to the UNC emergency room.

There, I got a tiny dose of good news. Having spent the day dreading getting stuck in the ER waiting room among slumped Vladimirs and coughing Estragons, I discovered that I was a heath care VIP. It turns out ER staff roll out the red carpet if you’re a middle-aged guy who shows up at midnight complaining of chest pains and coughing up globs of blood. You’re invited to step around the velvet ropes, past the sick masses. In minutes I had my own private booth, with a white-coated maitre d’ ordering for me off a menu of gourmet analytical delights — D-dimer and Troponin tests, CAT scans and more.

By 2am, my diagnosis was back: blood clots in my right lung, known to medicine as a pulmonary embolism, or PE. Though my PE appeared to be atypical or “unprovoked” — no surgeries, long flights, pregnancy, and I’m breathing fine (I think) with normal heart rate — the radiologists had seen several. Various blood tests corroborated the diagnosis.

I asked why I was hawking up blood. The doctor said when my pulsing blood hit the clots, there was enough back pressure to push blood out into the airways, where it gradually pooled until my lungs saw fit to hawk it up. And the jabbings were infarctions, basically tiny shrieks of lung tissue dying when it wasn’t get enough oxygen.

Yikes. Had I risked a stroke by not rushing to the hospital immediately?

No, said the doctor. I was relieved. He added, “PEs go to your heart. Heart attack.”

So my morning run was a bad idea? “Yes,” after microsecond of diplomatic pause (or incredulity?)

I was told to start taking a blood thinner immediately. “Xarelto. You’ve probably seen ads for it on TV.” Over the course of hours, days and weeks — no timeline can be guaranteed — my body would dissolve the clots and I’ll start feeling better. The risk of a heart attack goes down significantly — almost to zero — over the next 36 hours.

Death #1 averted.

I was told that there was nothing more to do that night. Though I stayed in my gurney, my heart rate and blood pressure leads were disconnected. After some paperwork, it would be time to go home.

Ever the skeptic and second-guesser, I had niggling doubts about this diagnosis. The nurse reiterated that the clots were in my right lung. I noted that the pain was all in my left rib cage, never in the right. I said I was still in significant pain and I don’t want to be discharged. She explained that internal pain is often displaced, since there’s no evolutionary reason for internal-organ-specific pain signals.

The nurse suggested a small injection of morphine. “This will take the edge off. When it wears off in 45 minutes, you can decide.” The end of the sentence — “to go home” — was unspoken, but strongly implied.

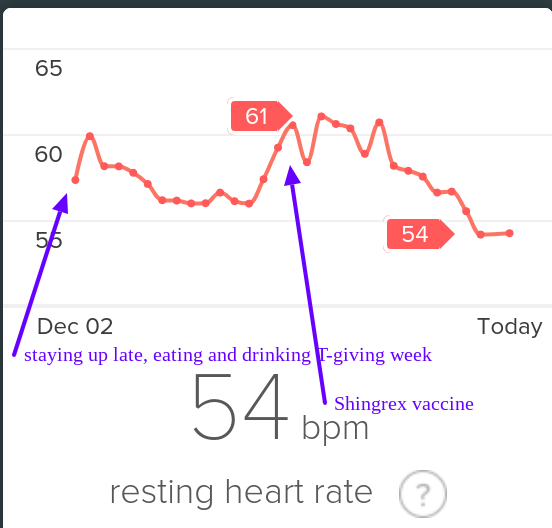

I bought a Fitbit Charge 2 in early 2017. In the Racery blog, I praised Fitbit’s insights into my heart rate, heart-rate variability and sleep stages. Fitbit revealed intriguing patterns. For example, I learned that (at least for me) staying up late eating and drinking beer elevates my resting heart rate for a few days — exactly as much as getting a cold or vaccination.

I even bought a sliver of Fitbit stock, figuring that even if the company fails to thrive, it has a high probability of being acquired for its hardware, patents, user base… and data. Fitbit’s ~$1.2 billion valuation seems like a drop in the bucket relative to the half trillion bankroll held by the likes of Google, Microsoft, Apple, and Amazon. Eventually, I upgraded to a Fitbit Ionic, which had enhanced heart rate monitoring.

At the same time, I became frustrated by what I could not do with my Fitbit data. When I tried to export the data, I learned that I would only access data per day or per run, and only in one month batches. (In November, 2018 this finally changed.)

To find patterns in the connections between my running, heart rate, and sleep, I wanted to export Fitbit’s raw intraday data to services like Smashrun, whose software creates marvelous graphs. Does my heart rate match my step count sometimes in the final miles of a long run, allowing me to accelerate by 1 minute per mile? How many total heart beats do I tally on a long run… or in a day or week or month? Unfortunately, Fitbit’s graphs are static and clunky, with the granularity of a color TV from 1971. In contrast Smashrun’s graphs are like a steadycam displayed on a 65″ 4G. Fitbit’s graphs are five minute aggregates; Smashrun’s are by-the-second.

Compare Fitbit’s static graph of resting heart rate (above) with the following animation of one of Smashrun’s interactive, multi-layered graphs.

I was frustrated to know that my granular intraday FitBit data WAS apparently accessible via companies like data aggregator Validic. But Validic’s customers are all businesses (insurance companies, drug companies) and it charges a minimum $10k year to deliver data for 2,000 people.

Strava, tightly focused on training needs of the athletic 1%, allows users to compare runs, but makes it hard to overview those runs.

Why, I wondered, couldn’t I easily access this data myself or pay a third party service like Smashrun to provide analytics?

I emailed Chris Lukic, Smashrun’s founder, with this question. He says he regularly encounters a variety of obstacles in integrating data from tracking devices and apps. He listed some of ways companies make data export harder than it needs to be:

- Create an API to allow access to the data, but restrict its use to “selected partners”. Then require those partners to make huge concessions — Garmin has a $5k fee, Strava reserves the option to request the data be deleted after transfer and to add their branding, Nike used to require you to give up equity in your company to use their API (through a partnership with Techstars)

- Allow data to be exported but make it inconvenient. Clicking on lots of links to export individual files. Companies very rarely allow “their” (your) data to be pushed to other systems.

- Fail to QA or bug fix data export formats. TCX and GPX files are the most common for running and heart rate. These formats are notorious for loose standards. Things like pauses, laps, descriptions, cadence, and heart rate data are defined differently by different apps. If the file imports “incorrectly” users almost always consider it the fault of the importing system rather than the exporting one. Runkeeper, for example went for years where there app would create exports with a UTC timestamp (which is correct), but their website exported files with a local time stamp. To get the time of an activity correct you needed to look for clues as to whether it was created by the app or the website, and then handle it appropriately.

- Provide only limited detail in exported formats. This might mean only exporting some fields (speed but not heart rate for example) or more commonly just reducing the dataset entirely. Runtastic for example might export only one out of every 10 data points recorded. Only enough to draw a map, but not evaluate the pace.”

Four stipulations:

Stipulation #1: I should have gone to the ER immediately after I coughed up blood. Not doing so was stupid and 100% on me. In light of the sudden appearance of blood, my assumption that my situation was non-acute (because of the months of accumulating tiredness and rib needling) was absurd.

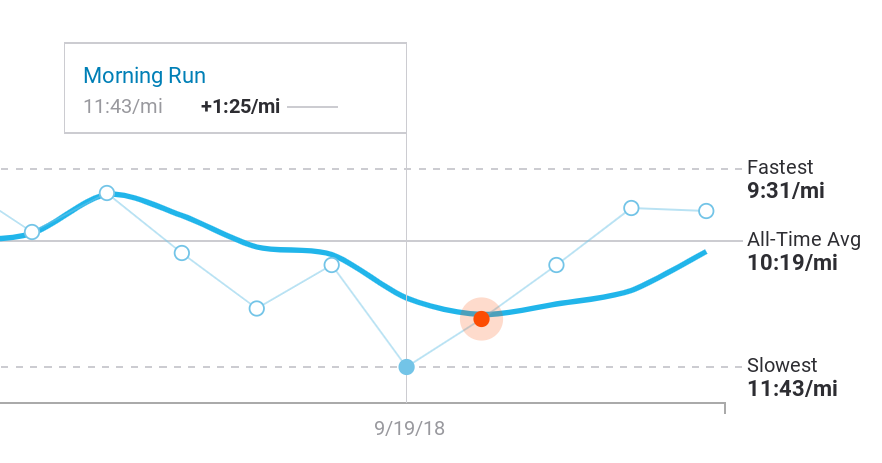

Stipulation #2: While I might have gone to the doctor months earlier and complained that I was “slowing down,” an email from Fitbit (or some third party service I might have hired to flag health developments) somewhere along the way saying “though your daily step counts indicate that you remain active, your pace during runs has slowed 20% in the last six months” would have been immensely helpful in jarring me out of my complacency, or denial. An enclosed chart would have, to boot, given me something to show a doctor.

Stipulation #3: Fitbit never promised to save my life. The company peddles fitness gadgets bundled with software for graphing and competition. (It does make occasional and very generic health recommendations: “walk another 75 steps to reach the healthy hourly goal of 250 steps!”) Fitbit’s site urges customers to “know yourself to improve yourself,” not to “track your heart rate to predict a cadiopulmonary disaster.”

Stipulation #4: I’m a middle-of-the-pack runner, doing 1–3 miles almost every weekday and trying to do 10–15 miles each weekend, if I can carve out the time. I run 3 or 4 races each year on trails rather than roads, and usually ignore my mile times. Aiming only to finish in the middle of the pack, I lack any consistent record of how fast I run miles. A diligent note taker — many runners are but not me — would have probably quantified the severity of my slowdown and taken action.

But I didn’t. And when I go back to look for evidence of my deceleration, the data that’s readily available in Fitbit is either far too detailed or way too zoomed out.

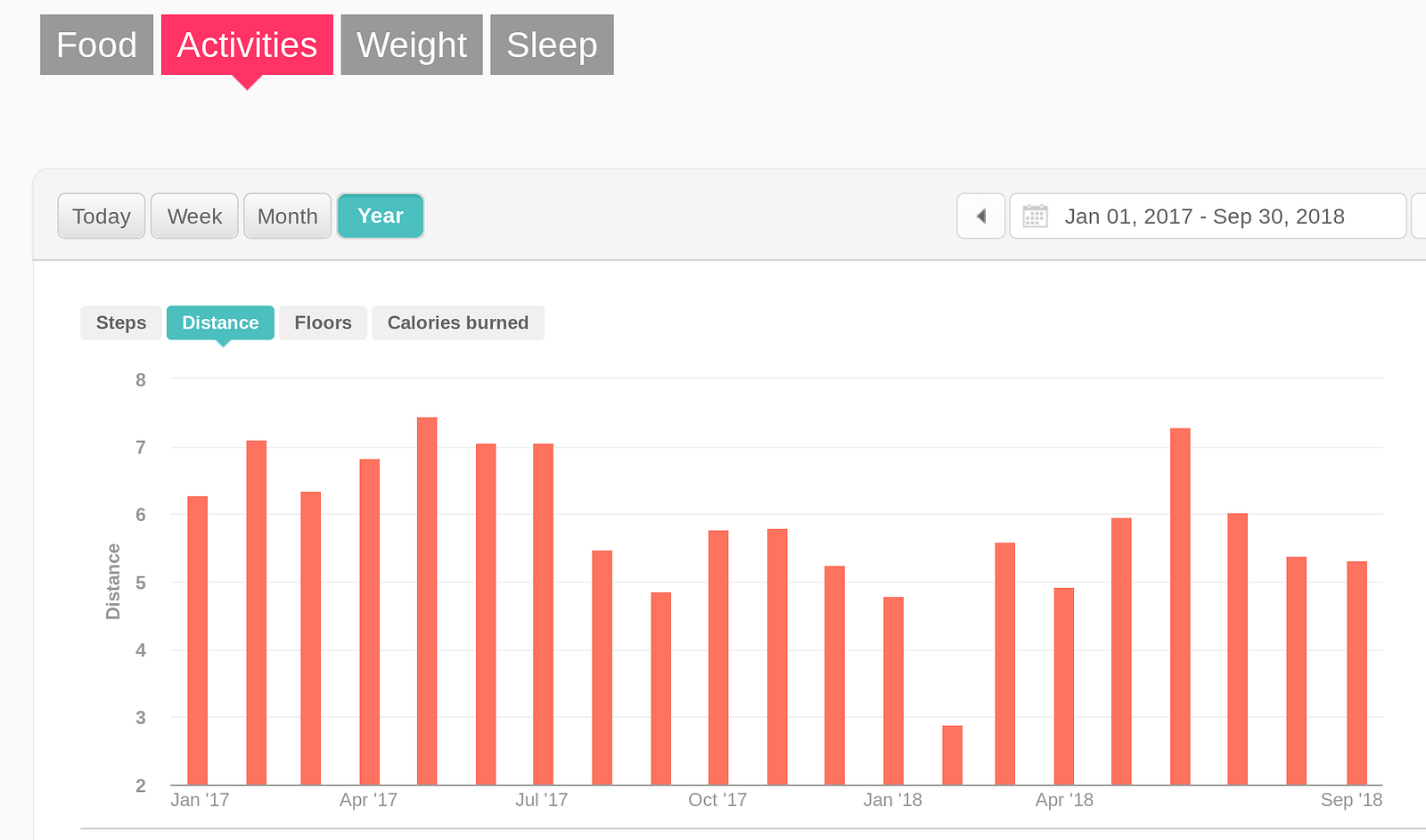

For example, when I look at per month totals, Fitbit offers blocky graphs relating to my food, sleep and weight, but that’s data I don’t care about about or, with the exception of sleep, could easily track myself in a notebook.

I’ve located some “big picture” graphs about my exercise, but they’re also not helpful. Consider, for example, the trendlessness of Fitbit’s graph (below) of the average number of miles I cover every day. Note that this is NOT the amount I’m running… its just the amount I’m moving. So, because I was increasingly substituting walking for running, the graph hides my downward health trajectory. Secondly, there’s no way to graph heart rate over that period — how many minutes per day was my heart rate elevated? What was my average heart-rate on runs? How often did I slow to a walk on long runs? Not possible.

As noted above, as 2018 progressed I’d sensed that I’d been slowing, but I never zoomed out to look for a pattern and, in Fitbit’s software, it’s not clear the pattern would have been visible no matter how I sliced the available data. It might have been easy to conclude that I was still recovering from a stress fracture in February that knocked me off trails and into the swimming pool for a month.

So that’s a Fitbit fail.

Casting about for other foreshadowings in the data, I go back and dig through various graphs in Strava, a racing app for cyclists and runners that imports data from Fitbit and other wearables. In Strava, I can only compare runs on specific routes. But at least in Strava I can see the actual slope of my declining health — nearly 20% from the previous April to two weeks before I started coughing up blood.

That particular slice of data is not available in Fitbit’s graphing toolkit, and is only buildable in Strava with a lot of digging and prodding.

Again, my blindness (or denial) about my own declining cardiovascular health and its potentially devastating implications for my longevity are entirely on me. I’m writing here to note that the fitness device industry, and Fitbit in particular, is missing an opportunity to help prolong the lives of idiots like me. And maybe make some money along the way.

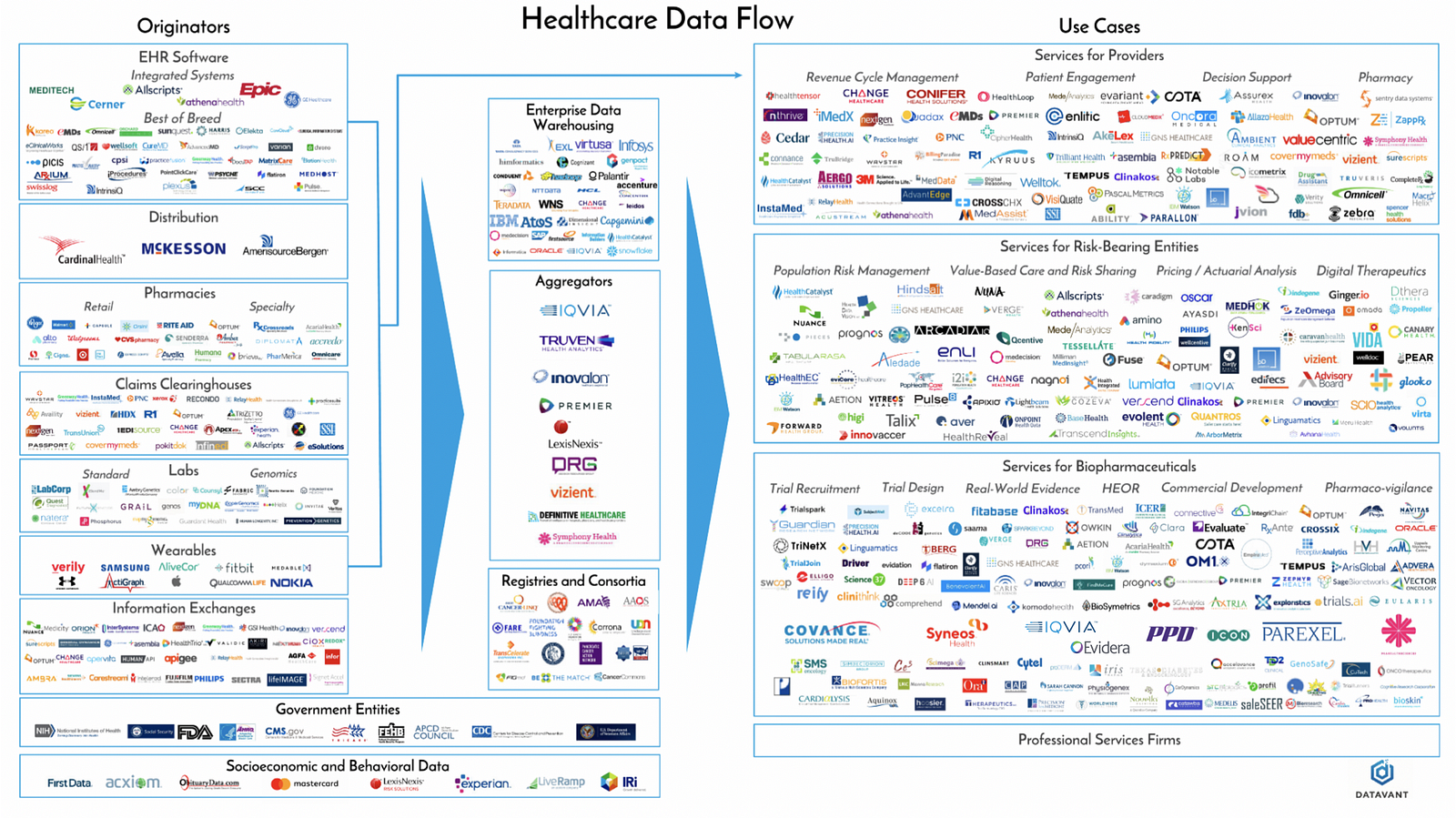

My difficulty accessing and analyzing my own fitness data is grain of sand in a Sahara of systemic failures, shortfalls and dysfunctions in how health data is generated, stored, shared and processed. Those dysfunctions include:

- Health data is fragmented and sequestered among a long list of providers, systems, devices, institutions, organizations.

2. Not only are the number of producers and processors of data growing yearly, volume is exploding too. According to Datavant, “The healthcare system generates approximately a zettabyte (a trillion gigabytes) of data annually, and this amount is doubling every two years.”

3. Even as technology’s capacities — storage, processor speed, algorithmic efficiency and subtlety — expands 100-fold each decade, it is still steered by humans — fragile tissues of self-serving biases and beliefs embedded in institutions that are, above all, bent on survival and self-celebration. What does this mean practically? Though medicine today aspires, more than any other industry, to promote human health, it still takes decades for doctors and med schools to move on from disproven treatments and devices. It took 150 years for physicians to accept that thermometer was superior to human touch, and change remains “generational,” according to Dr. David L. Brown, a professor in the cardiovascular division of the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. Doctors remain exceedingly loyal to the techniques and technology they rode in on, particularly when the practices help pay bills. (Brown is co-author of a meta analysis that examined all current studies of stint implantations in treatment of stable coronary artery disease. Though stints provide zero benefit to patients who are not suffering a heart attack, hundreds of thousands of stints are implanted, each with a 1 in 50 risk of serious complications.)

4. As each organization competes to extract its own smidgen of insight, profit or leverage from the data it creates or touches, it mangles the data slightly, whether inadvertently or intentionally, to fit its own needs with omissions, concatenations, mergers, nonstandard labeling, units or time series. This goes from individual studies, in which goalposts are regularly moved (an example) or data is “lost,” to larger analyses, in which inconvenient data is systematically elided, to medical journals themselves, which former editor of the New England Journal of Medicine Marcia Angel argues have been manipulated to the point of shilldom by the drug industry.

5. Then there’s the FDA, the agency that regulates US medicine and devices. On the one hand, the FDA is the consumer’s best defense against huckers peddling sham science — sugar pills or worse sold to desparate patients and credulous doctors (or impatient patients and quacks.) On the other hand, some argue the FDA raises the cost of innovation and kills potentially life-saving drugs. Regardless, the billion-dollar-plus cost of developing new drugs and regulatory barbed wire inherently favor existing, highly capitalized drug companies over upstart developers of cheap, common sense solutions.

The FDA, which originated in the late 19th century as the “Bureau of Chemistry,” has evolved as a creature within a complex interlocking ecosystem made up of PHARMA, researchers, med schools, doctors, legislators and lobbiests. Most of its staff have worked in multiple roles across the ecosystem — they’re imprinted with the same DNA, an atomic paradigm of health.

At roughly 3am, the nurse comes into my little cubicle to ask how I’m feeling post morphine injection.

She notes, once again, that I’m cleared to go home. The forms are ready. Nudge, nudge. Ready?

(In retrospect, I was now — in the staff’s collective medical wisdom and probably explicitly declared to be so in the charts — a “solved” case who was clogging up an emergency room bed that could be given over to someone in the waiting room. ERs are paid to “turn” beds.)

I tell the nurse that I’m still in significant pain. In fact, I’m feeling kind of clammy.

Woozy even. The pain is increasing? In fact. Excuse me, nurse. I need a bucket. I’m feeling nauseous.

My sense of pain and general unease gathers into a feeling that something’s happening that I don’t understand.

You’re very pale, says the nurse.

She reconnects my heart monitor leads. My heart rate is 55 beats per minute.

And then it’s 50.

Then 45.

Suddenly my little bay starts to fill with the cast of nurses, orderlies and the junior and senior doctors I’d seen on stage at various times earlier in the evening. Maybe ten of them in all… why?

40.

You’re white. How are you feeling?

Kinda woozy. Crappy, actually.

35.

My HR seems to be dropping 5 bpm each quarter minute. Sweat is dripping off my face and neck, pooling where my chest meets my stomach. I’m wishing I could see my kids. To say goodbye?

30.

I muse: if this is death, where are the lights and tunnels and trumpets?

Someone is placing two palm-sized, wired, adhesive pads on my upper chest. Shock paddles.

Standing at the foot of my gurney, the senior doctor tells me to keep updating him on what I’m feeling.

Well, my eyesight is getting fuzzy.

And now I can’t see you.

25.

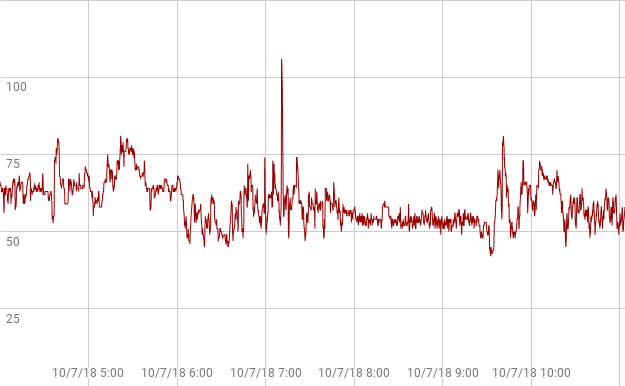

So that’s the second time FitBit was mute when it might have helped keep me alive, or at least warned me and my doctors that I shouldn’t drive home.

Could Fitbit, or some service accessing my data with my permission, have sent out a distress signal before my heart-rate started dropping 5 BPM every 10 seconds? Recent research suggests that panic attacks, long thought to be spontaneous responses to external cues, may be foreshadowed in autonomic data by as much as three-quarters of an hour. But it will be a LONG time before any tools are available for my problem, or those of panic attacks.

To date, researchers have published 675 health studies based on subjects outfitted with FitBits.

That’s stupendous, but it’s also trivial compared to the potential research that could be done. FitBit’s terms of use state that Fitbit owns all “Fitbit Content,” which includes any “data” “generated” with its software. I own my heartbeat, Fitbit owns my 0s and 1s. And Fitbit squats on the motherload of health data — all the data from all the Fitbits.

Fitbit’s nonchalantly selfish stewardship of our (my!) immensely valuable data is on prominent display when company staff boast about Fitbit’s scientific value. “We’re in this unique position of having access six billion nights of sleep data, and this is an area we haven’t done much yet,” Fitbit’s director of data science, Hulya Emir-Farinus told gadget guru David Pogue in an August, 2018 interview.

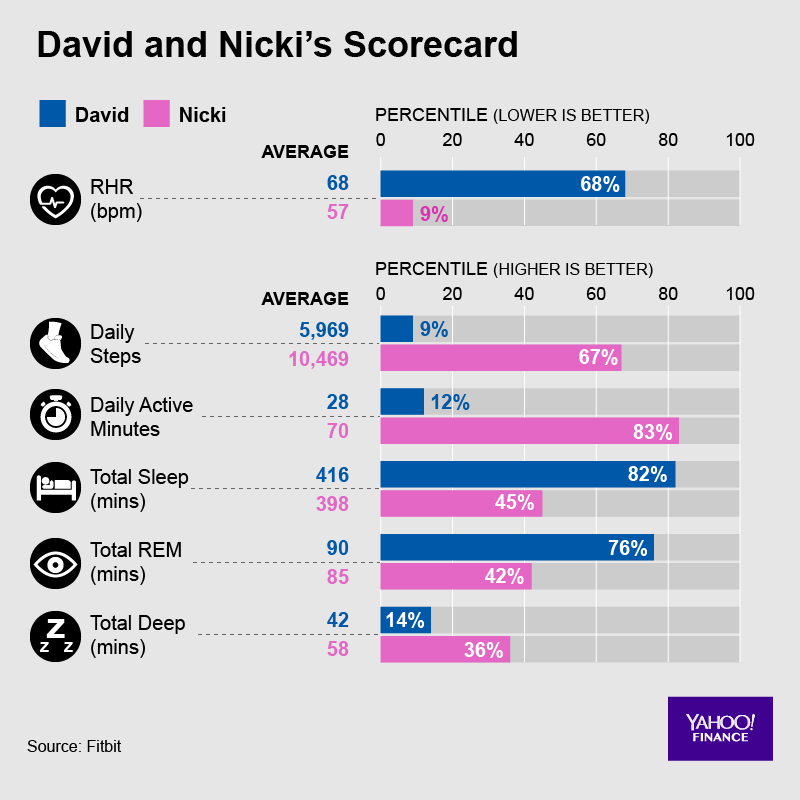

Fitbit gave Pogue an “exclusive deep dive” into 150 billion hours of heart rate data, which contained fascinating insights. For example, Fitbit’s data shows that an inactive 45-year-old man can drop his resting heart rate (RHR) by 5.5 beats by doing 40 minutes of exercise daily. But a 75-year-old who excercises 40 minutes a day has a RHR that’s less than 2 beats per minute lower than his innactive buddy’s. (Why does this matter? A lower RHR correlates strongly with lower risk of dying.)

Wouldn’t you love quantification of the relationship between your own daily exercise minutes and your resting heart rate? If your rate is higher or lower than average person, that might suggest something about your overall health or longevity. Sensing the value of this relative information, Fitbit gave Pogue details about where he and his wife sit in the bell curve of Americans for HR, sleep and steps. (Below.)

But the rest of us, who contributed the data, will have to wait to take our own look at the data.

I’m told that, at around 20 BPM the morning of October 7th, the senior doc told a nurse to inject atropine, which takes the brakes off your heart-rate. I remember (or imagine) a jab in my left shoulder. 1.5 milligrams? (I don’t see any record in the online health record UNC provides.)

When I was again alert — was it 15 seconds or two minutes? — my gurney was in central work space, which I was told gave the staff more room and equipment for emergency procedures… if those became necessary… in another 20 heart beats or so? In any case, the shock paddles weren’t used, which friends now tell me could have been very painful.

The conclusion? “We’re not exactly sure what happened, but are pretty sure it’s not caused directly by the PE. In short, we think you were fainting.” No medical professional — friends who are nurses and doctors — I’ve talked to since has had a better explanation. My subsequent conclusion — you know I was a Boy Scout, right? — was that my body was rebelling against a combination of 36 hours of pain, sitting up in the bed with not enough blood going to my brain, my lung(s?) dealing with puddles of blood, the intensified misery of lying in the CAT scan, being cold, the morphine jab (or its ebb?). Who knows.

If it was “just” fainting, the heart rate collapse probably wouldn’t have killed me outright, but might have been disasterous had I’d been driving home at the moment it happened. In any case, the ER doctors reversed course on the discharge order, and decided to keep me in the hospital for observation.

I dozed in the ER bed until 10am waiting for space to clear up in the hospital’s observation unit. By midday, my rib jabbings were, as predicted, slightly fainter. The blood thinner was already working. Two weeks later, blood no longer gurgled in my throat when I coughed. I realized one morning in November that, at some point in recent days, I had stopped feeling the jabs, even during my biggest inhales. Tests for various cancers — apparently the smoking gun for 10% of unprovoked PEs — came back with no hints of cancers.

A a couple months later, after lots of clicking around on Fitbit.com and reading forums, I learn that Fitbit has expanded its data access from the prior one-month-only single-point-per-day data dumps. Though the new data access was not real-time, and many users are frurstrated by the new format, I can get the data I wanted. I downloaded a big file, downloaded a third party tool that converts file formats ($10/month), dumped the results of that conversion into a Google spreadsheet, dug some, figured out how Fitbit’s time-stamps convert to my local time, then used some graphing software. After 45 minutes of reading, digging and tinkering, I finally managed to dig produce a snapshot of the incident. Here’s what I saw.

Obviously Fitbit failed to capture the full collapse the hospital’s heart monitor had captured. My wrist was too sweat-drenched? Fitbit discarded the data because it appeared so abnormal? Was there a clue of what was to come — as with panic attacks — in the smooth decline of the prior 90 minutes leading to the accelerated slide? Until Fitbit asks the question of its millions of data points — or lets me ask the question of my own data — we’ll never know.

As 2019 progresses, I’m told I may be on blood thinners for the rest of my life, since going unmedicated gives risking a 30% chance of clots over a five year period. (Medicated, my odds of a PE are 1 in 60 per year.) I’m back to doing 30 minutes of 9.5 minute miles, and sometimes 6 miles with only a minute or two of walking on steep hills. And I’m still wearing my Fitbit Ionic, though the band is failing badly.

INDEX

Prologue: Two times Fitbit didn’t save my life; my six month journey on the borderlands of my own health data.

Part 1: My night continues downhill. Fitbit’s muteness gets louder.

Part 2: 23andme detects no clotting genes; demand for genetic expertise outpaces supply; DNA surprises about my personality and eating habits.

Part 3: A cartoon of the future of the medical industry.

Part 4: Five categories of predictable exponential tech change: devices, granularity, volume, utilization, software.

Part 5: Two categories of unpredictable change: the demands of individuals and their communities.

Part 6: Medicine, already trailing state-of-the-art techniques and technology by 17 years, gets lapped.

Part 7: Like fax machines, newspapers and encyclopedias, is medicine another information processing machine on the verge of being disintermediated by mutating consumer demands and tech innovation?

Part 8: Ten possible frontiers of consumer-led healthcare change.

Well Henry as always a fun read . Also informative . I only rely on my Fitbit for steps . I use something else to monitor my HR . And monitor the BP daily . I’m not a runner , but ride much and do spin classes regularly . I also lift . My cardiac nurse daughter ever the diligent one to lecture .

Please continue to care for yourself in this new fashion .

Thank you Sharon! Glad to hear your a device fiend too.