Recently I spit into a little plastic tube and sent it off to 23andMe.

I sprang for the $200 DNA test because it was a fast, affordable way to detect genes relating to hereditary thrombophelia — a tendency to clot. I was interested because, in early October 2018, I had experienced a pulmonary embolism — in layman’ terms, clot(s) in a lung.

My primary care physician, a smart doctor a decade out of med school, had been “meh” on prescribing a genetic test. When we first talked, the week after I’d gone to the ER coughing up blood, he’d said my insurance probably wouldn’t cover the cost. Besides, the test results — positive or negative — wouldn’t be actionable. He also thought a consumer genetic testing service like 23andMe didn’t offer the specific test I wanted.

A few weeks passed. Tests for various cancers that sometimes trigger excess clotting — colon, prostate and lung — came back clean. My PE was categorized as “unprovoked,” which is medicine-speak for “no clue.” I was told I’d need to take prophylactic blood thinners for a long time, perhaps the rest of my life. (Some relevant stats: 1–2% of PE first-timers die. After the first PE, without blood-thinners, the five year odds of a reoccurence are 1 in 3. Mortality is higher for relapsers.)

So I started thinking about the gene test again. I was curious because identifying a guilty gene — hematologists look at the eFactor V Leiden variant in the F5 gene and the Prothrombin G20210A variant in the F2 gene — would provide both a smoking gun and a heads up for my kids.

I did some Googling. I learned that, since mid-2107, hereditary thrombophelia is one of nine “health predisposition” reports offered by 23andMe. (Ten, as of 2/27/19; eleven as of 3/10/19.) Since I’m less than a decade from Medicare and already have life insurance, I decided to take the plunge.

A few weeks later, 23andMe sent me an email with a link to my results — negative for clotting genes. No smoking gun. Cross that suspect off my list.

Since then, I’ve been trading emails with friends about various aspects of gene testing, particularly when done by consumers. Some of what was in those emails — thank you Tina, Brent, Corrine and Christian! — gets strung together below. I’m also indebted to Azeem Azar’s Exponential View newsletter, which I read almost every week.

Until 2013, 23andMe offered genetic reports on 254 diseases and conditions. But that November, after months of 23andMe ignoring repeated FDA requests for information, the agency stopped barking and bit. Declaring that 23andMe’s reports amounted to “medical devices” that required “premarket approval or de novo classification,” the FDA barred the company from offering any genetic reports relating to health.

Now, after years of 23andme’s concerted obeisance to the FDA, the company is allowed to offer eleven “health predisposition” reports, plus an additional 44 “carrier status” reports.

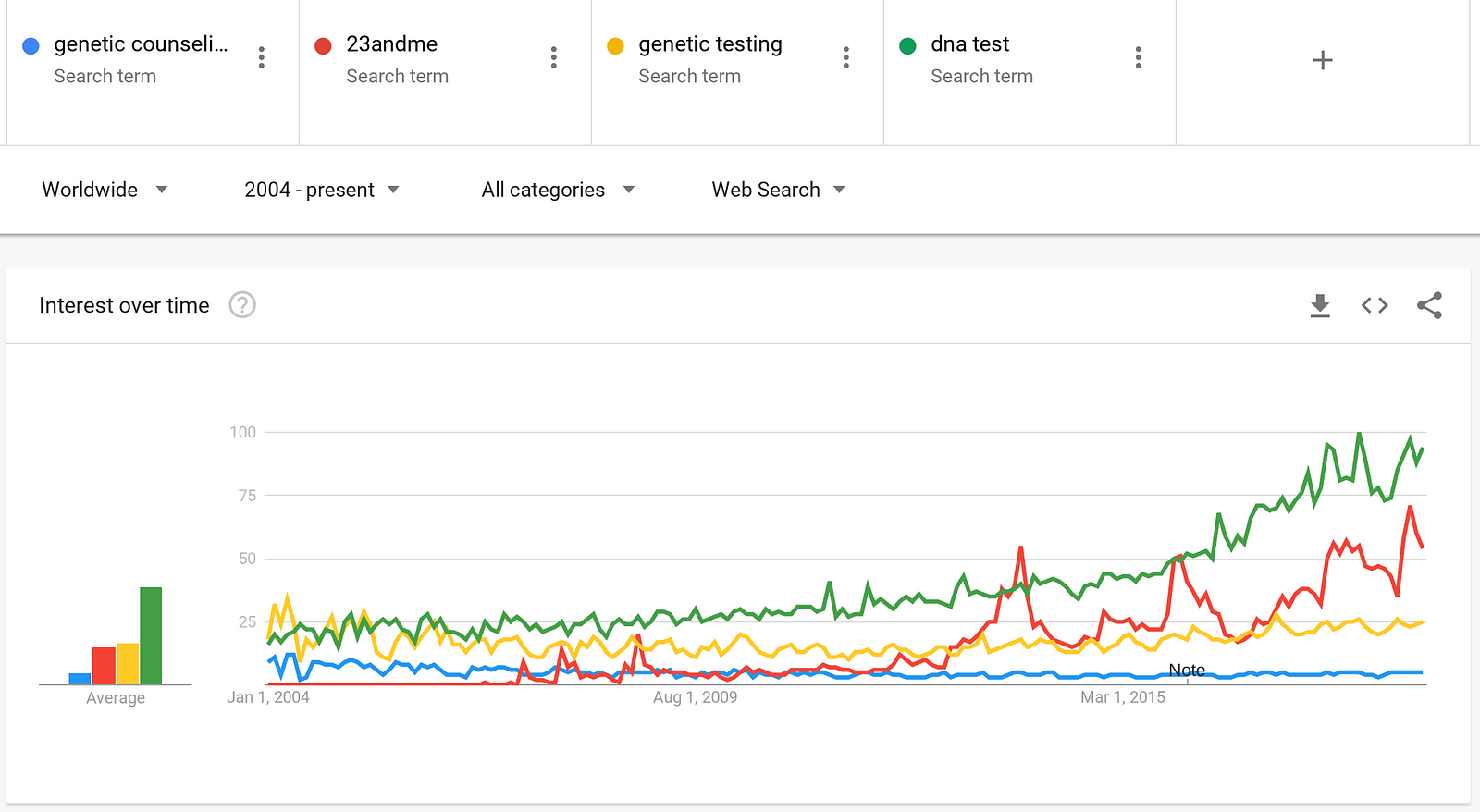

Despite the FDA’s bar on 23andMe’s provision of health results, consumer demand for genetic testing just kept rising. Searches relating to DNA testing now far exceed searches for conventional genetic counselling. If you’re curious about your DNA, Google is the new waiting room.

And while doctors, journalists and regulators obsess about 23andMe, 10 seconds of Googling summons numerous alternative services that offer genetic data relating to thousands of health conditions (from diabetes to schizophrenia) and drug responses (from lithium to insulin.) Many of these services, run by scientists building on NIH databases and open source software, are free or low cost.

My friends have asked about my DNA testing, so I’ve written a brief tour, both off-piste and official, of my results.

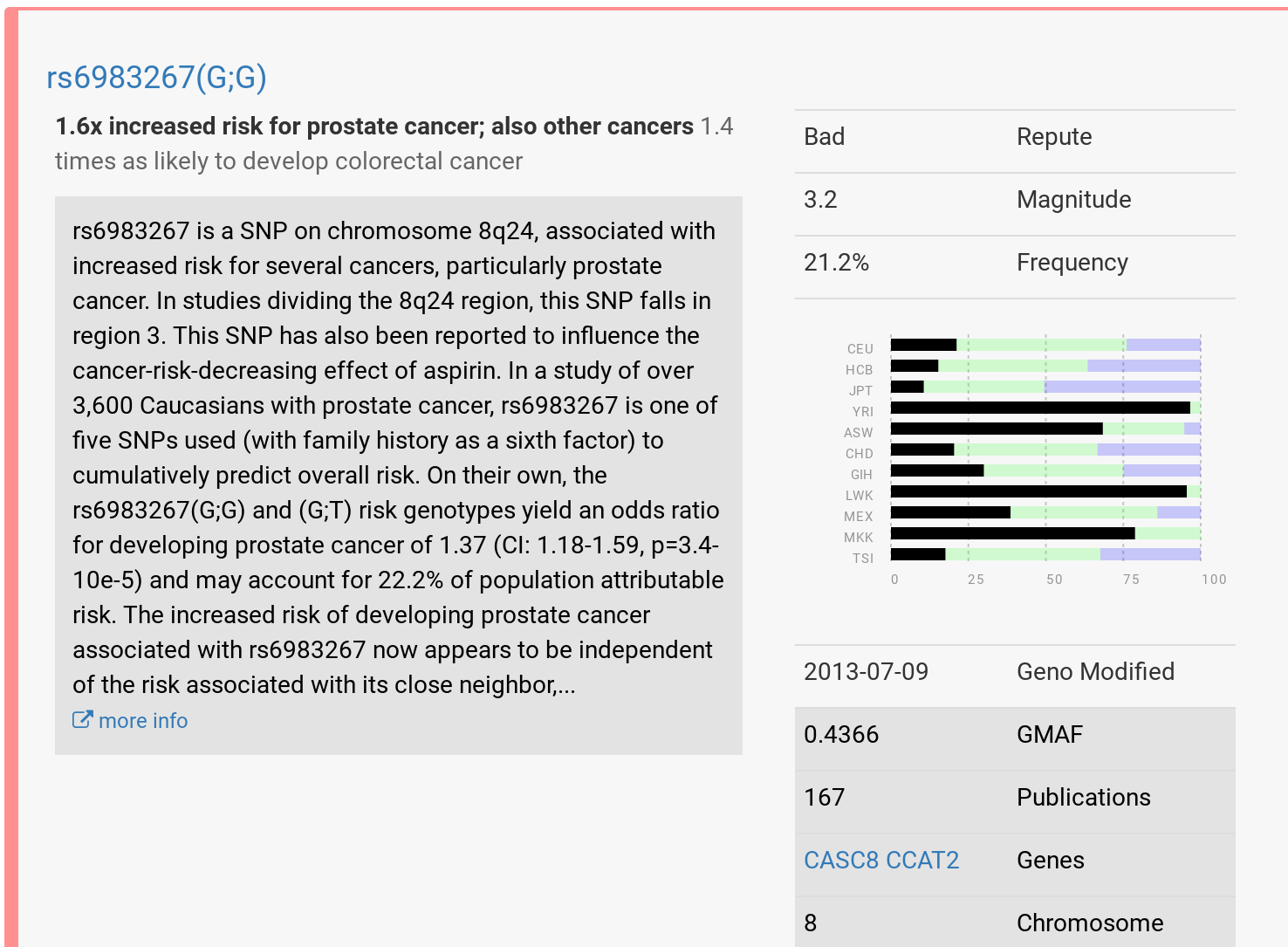

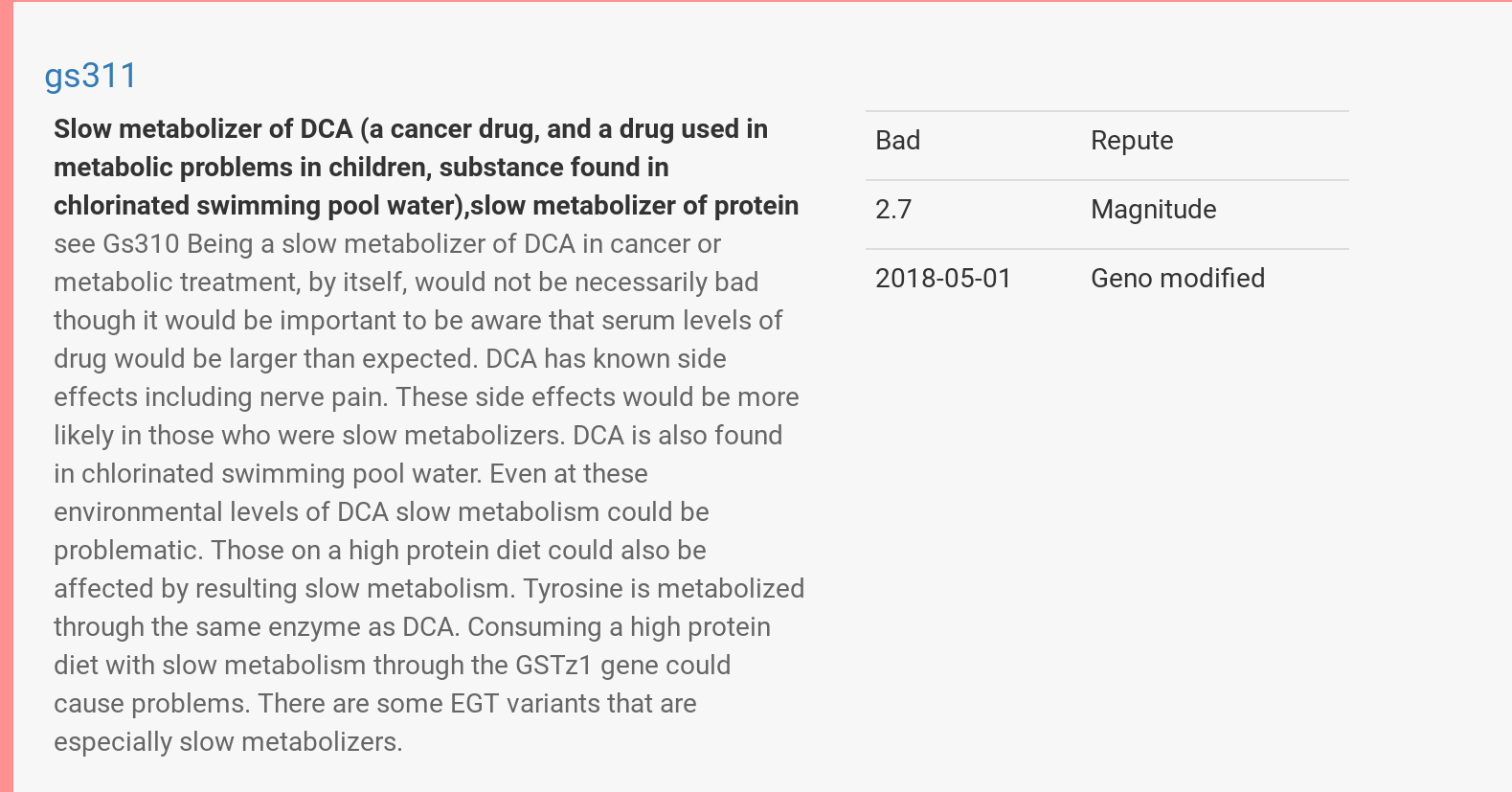

So far I’ve tried promethease.com and impute.me after uploading a file I exported from 23andMe. The reports I got back, with each SNP or cluster of SNPs linked to peer reviewed research, are incredibly rich. (SNPs are “single nucleotide polymorphisms,” the smallest unit of genetic testing.)

My Promethease results for SNP rs6983267 look interesting, but since I recently had a prostate test, they’re not actionable…

On the other hand, my Promethease results for gs311 might be useful if I had cancer and was due to be treated with DCA. (Or if I was tempted to eat a cheeseburger while swimming at a public pool.)

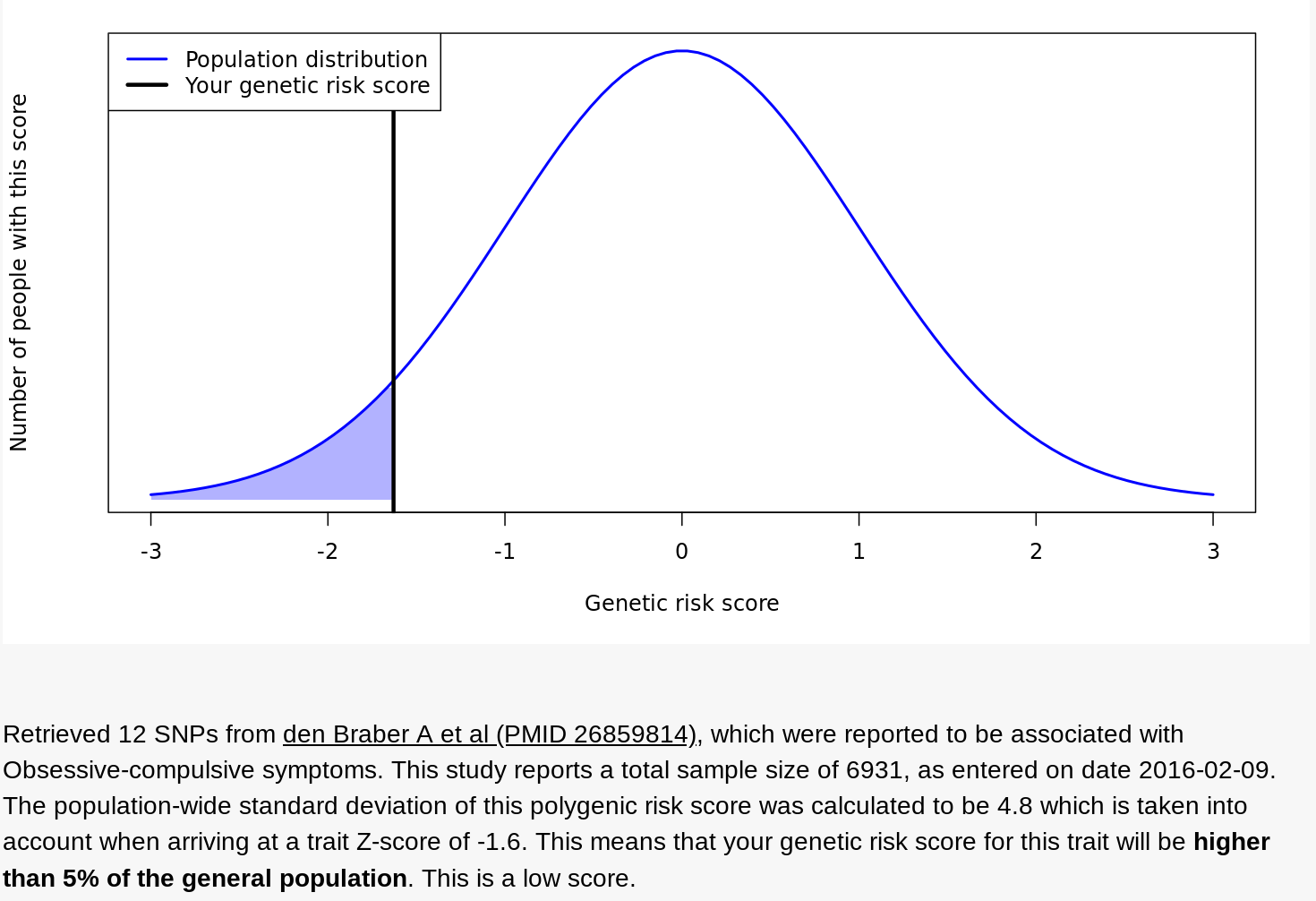

Impute.me offered another view — a holistic analysis of clusters of SNPs that various pieces of research associate with what the site calls “complex diseases.” For example, here’s my data for a group of SNPs that, at least according to one 2016 study of 6,931 people, correlates with a diagnosis of obsessive compulsive disorder. Seems I’m less genetically predisposed to OCD than most.

Finally, something relevant, at least for my dating life: I have the AG genotype for Rs53576, a section of the oxytocin receptor (OXTR) gene. Recent research correlates the AG genotype with being less empathetic (leading to a 4% reduction in marital satisfaction!) at least in comparison to the GG type. The good news, one study showed that social support lowers AG’s cortisol in stressful situations, at least relative to AAs; another study showed that AGs being more sympathetic to racial outgroups than GGs or AAs. (In the US, 41% are GG; in Africa, 65%; in East Asia, 12%, according to Selfdecode.com.)

23andme emailed a few days ago, subject line “Your new Type 2 Diabetes report.” I clicked and learned that my “genetics are associated with an increased likelihood of developing type 2 diabetes.” My odds were 30% in the next 30 years, “higher than typical,” according to 23andme. But I already knew that from both Promethease and Impute.me.

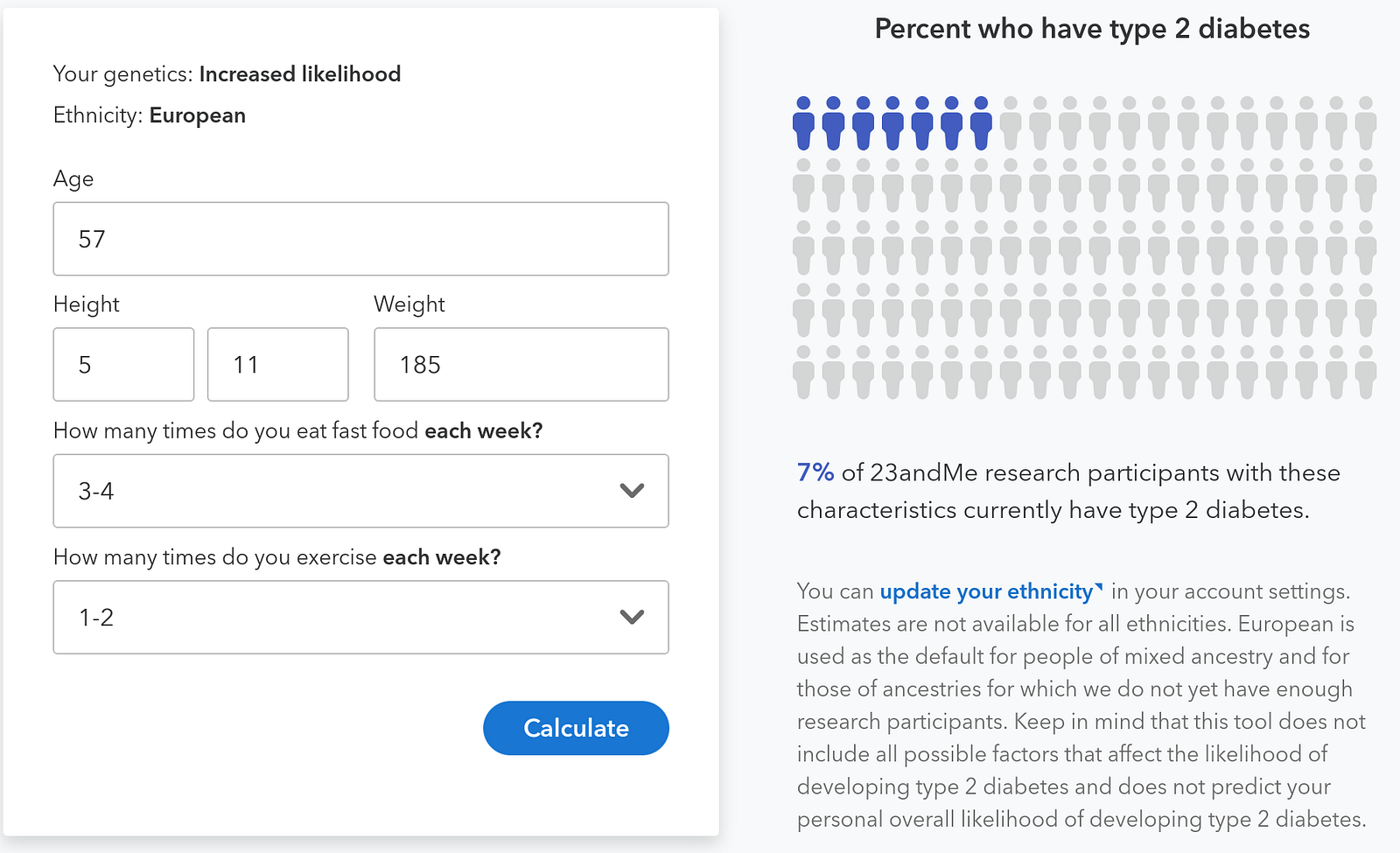

What’s news is that 23andme has, based on lifestyle surveys of its customers, quantified how weight, exercise and fast food consumption interact with my genes. 23andme reports that, using data from 2.3 million customers, it discerned 1,000 genetic variants that could be used in assessing individual risk scores. (Here’s 23andme’s whitepaper on the work.)

Playing with 23andme’s predictive widget, I’ve learned that losing 15 pounds could cut my risk of type 2 diabetes from 3% to 2%. Conversely, raising my weight by 15 pounds would boost my risk to 4%.

Switching from my current regimen (let’s call it “max health” — zero fast food and exercise seven times a week) to a weekly regimen that’s “typical” — eating fast food 3–4 times, exercising 1–2 times — more than doubles my risk of type 2 diabetes, even if my weight doesn’t change.

Comparing results with a friend, I’ve confirmed that risks are very different for people with different genetic profiles. She currently has just a 1% chance of diabetes. That’s not just because she’s in her 30s and lighter than her peers. Adjusting her model to match my age and weight-relative-to-peers, her risk of type 2 diabetes is 33% lower than mine under “max health” scenario and 43% lower in the “typical” scenario. Pretty amazing to see the differences in our metabolisms so exactly quantified!

The classic rap on gene tests has been that they don’t yield actionable information. I’d say those days are over. I’ve now learned that I require more exercise and less fast food, relative to my peers, to reduce my already high odds of type 2 diabetes. Visiting Wendy’s once or twice a week is a LOT less tempting after the latest 23andme report.

Read next: Part 3: A cartoon of the future of the medical industry.

INDEX

Prologue: Two times Fitbit didn’t save my life; my six month journey on the borderlands of my own health data.

Part 1: My night continues downhill. Fitbit’s muteness gets louder.

Part 2: 23andme detects no clotting genes; demand for genetic expertise outpaces supply; DNA surprises about my personality and eating habits.

Part 3: A cartoon of the future of the medical industry.

Part 4: Five categories of predictable exponential tech change: devices, granularity, volume, utilization, software.

Part 5: Two categories of unpredictable change: the demands of individuals and their communities.

Part 6: Medicine, already trailing state-of-the-art techniques and technology by 17 years, gets lapped.

Part 7: Like fax machines, newspapers and encyclopedias, is medicine another information processing machine on the verge of being disintermediated by mutating consumer demands and tech innovation?

Part 8: Ten possible frontiers of consumer-led healthcare change.