Though doctors and drug makers tout “average” effects, many treatments deliver a smorgasbord of results—substantial benefits for some people, little benefit for many, and harm for a few. Why don’t we hear more about this variability?

Roughly a century ago, modern medicine got off to a roaring start. Pasteur discovered the bacterial origin of many diseases in 1870. Handwashing reduced deaths from surgery and childbirth. Antibiotics cured many infections. Vaccines wiped out polio, smallpox and chickenpox. Starting in the 1920s, insulin significantly prolonged some lives.

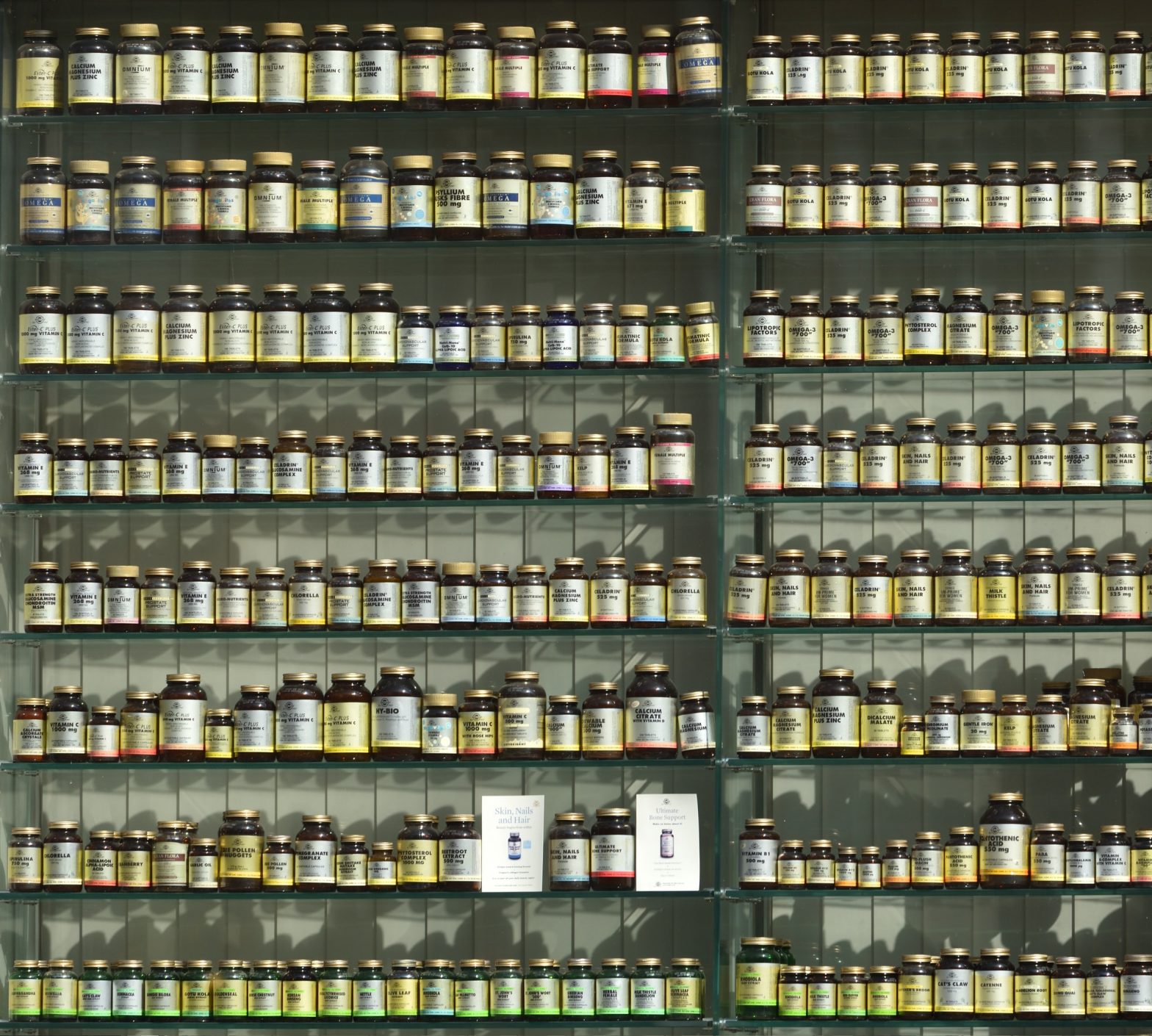

Since then, though, momentum gradually has slowed. Humans are vastly complex biological systems. We’ve discovered that, for chronic conditions like Parkinson’s, arthritis, Alzheimer’s, IBS, migraines and psoriasis, the effects of a given treatment vary depending on the patient. As one analysis in 2011 put it, “the development of medical interventions that work ubiquitously (or under most circumstances) for the majority of common chronic conditions is exceptionally difficult and all too often has proven fruitless.”

Researchers call a treatment’s variable effectiveness per individual its “heterogeneous treatment effect,” or HTE.

Though HTE is what’s meaningful for most patients— nobody is actually average, right?—it’s usually unmentioned in publicity for treatments.

This is because, as Richard L Kravitz, Naihua Duan, and Joel Braslow explained in a 2004 paper, treatment effect averages are the “primary focus on clinical studies in recent decades.” The average effect is what researchers look for, what the FDA approves, what drug companies promote, what doctors base prescriptions on, and what patients expect.

But, as the 2004 paper noted, the modest average effects everyone focuses on may, in fact, mask “a mixture of substantial benefits for some, little benefit for many, and harm for a few.”

There’s a second error that results from focusing on a drug study’s reported average effects, they argued. Heterogeneity “may be dramatically underestimated” because “by convenience, randomized control trial are characterized by narrow inclusion criteria and recruitment.”

In fact, “nonrepresentativeness is probably the rule rather than the exception.” Put simply, the people in a drug study often don’t reflect a population’s full diversity of race, sex or health conditions.

Kravitz, Duan, and Braslow explained that though the generalizability of a large drug trials is often relatively weak, average findings are often quickly distilled into treatment guidelines, and these, in turn, can too easily creep into rigid treatment standards. Harm can result. For example, a drug trial for a diuretic called spironolactone seemed to show a 35% benefit for the average patient, but when included in treatment standards resulted in a four-fold increase in hospitalizations and no reduction in all-cause mortality. Significant groups had been underrepresented in the original trial.

Attention to HTE probably won’t change any time soon. Unfortunately, “the pharmaceutical industry currently has little direct incentive to collect data on risk, responsiveness, and vulnerability that would better inform individual treatment decisions,” according to Kravitz, Duan, and Braslow. In fact, mass market economics incentivize one-size-fits all treatments, since doctors prescribing based on “average” results create far larger markets for drug makers.

An additional problem when evaluating HTE: the deck is stacked in favor of a positive results in most published randomized control trials.