Diagnostics and treatments already lag best practices by 17 years

Given these cascading exponential changes, what might we say about the future of US healthcare, beyond the most obvious — expect the unexpected?

Let’s start with the effect of this multi-dimensional convergence of change shock waves on the existing US medical industry.

First, obviously, many innovations will be readily integrated by the industry. Exponential improvements in hardware and software will augment rather than cannibalize existing services. Some examples of improvements that will simply “bolt in” to the existing infrastructure include:

- software that predicts survival rates for patients with ovarian cancer four times more accurately than doctors.

- genomics that help tailor the mix of drugs targeting pancreatic cancers.

- software that precisely diagnoses sepsis in newborns.

- software that analyzes doctor’s notes to predict psychiatric crises better than the doctors themselves.

- improve on breast cancer diagnostics for bottom 50% of radiologists.

- software that reduces the number of false positives on lung cancer scans.

But the number of innovations that are adopted will be dwarfed by those that are wait listed and back ordered.

Part of the problem is structural. The industry is a continent-spanning Rube Goldberg machine cemented together by crazy glue. It is almost as complex as its putative subject, the human body. It’s comprised of a matrix of institution (hospitals, insurance companies, drug manufacturers, med schools, device makers, regulators), individual roles (general practitioners, nurses, physicians assistants, physical therapists, regulators, administrators, technicians, insurance coders, researchers, salespeople of all stripes, specialists) and informational sockets (pricing, practice, process, billing code, training, diagnostic procedure, testing protocol, delivery method.) Any change in one node usually requires coordinated concurrent changes spanning multiple other nodes. This complex interdependence means stasis or gridlock are its default modes.

Trying to bridge the gap between what the system permits and patients want, humans are stretched to the breaking point.

There are already far too few genetic counselors to keep up with demand, with growth impeded various state-by-state regulations. Doctors are overwhelmed, now spending twice as much time on paperwork than with patients. As one doctor explained:

Like some virulent bacteria doubling on the agar plate, the [Electronic Medical Records] grows more gargantuan with each passing month, requiring ever more (and ever more arduous) documentation to feed the beast. …

To be sure, keeping electronic records has benefits: legibility, electronic prescriptions, centralized location of information. But the E.M.R. has become the convenient vehicle to channel every quandary in health care. New state regulation? Add a required field in the E.M.R. New insurance requirement? Add two fields. New quality-control initiative? Add six.

Medicine has devolved into a busywork-laden field that is slowly ceasing to function. Many of my colleagues believe that we’ve reached the inflection point at which we can no longer adequately care for our patients.

But shortages of skills and hours are just two of many factors constraining the medical industry’s ability — or desire — to keep up with healthcare innovation.

Doctors argue that this system’s reticence serves to protect patients from quack science. But sometimes their foot dragging grows from egotism or financial self-interest. In the late 19th century, many doctors fought the professionalization of nursing, lest the new players harm the incumbents’ livelihoods and authority. The guild’s interests haven’t changed. Just 40 years ago, pregnancy test manufacturers held off on launching home tests for fear of offending their traditional customers — doctors. Even after home tests became available in 1977, some doctors continued to resist.

…the Texas Medical Association warned that women who used a home test might neglect prenatal care. An article in [The New York Times] in 1978 quoted a doctor who said customers “have a hard time following even relatively simple instructions,” and questioned their ability to accurately administer home tests. The next year, an article in The Indiana Evening Gazette in Pennsylvania made almost the same claim: Women use the products “in a state of emotional anxiety” that prevents them from following “the simplest instructions.”

Stents are another example of the sticky status quo. Stents are apparently ineffective in all but extreme cases of heart disease, a 2011 article in the Journal of American Medical Association argued that more than 70,000 unnecessary stent implants were being performed annually in the US, despite the fact that 3% of patients experience serious complications.

Doctors are human, exhausted creatures habit and foibles:

For all the truly wondrous developments of modern medicine — imaging technologies that enable precision surgery, routine organ transplants, care that transforms premature infants into perfectly healthy kids, and remarkable chemotherapy treatments, to name a few — it is distressingly ordinary for patients to get treatments that research has shown are ineffective or even dangerous. Sometimes doctors simply haven’t kept up with the science. Other times doctors know the state of play perfectly well but continue to deliver these treatments because it’s profitable — or even because they’re popular and patients demand them. Some procedures are implemented based on studies that did not prove whether they really worked in the first place. Others were initially supported by evidence but then were contradicted by better evidence, and yet these procedures have remained the standards of care for years, or decades.

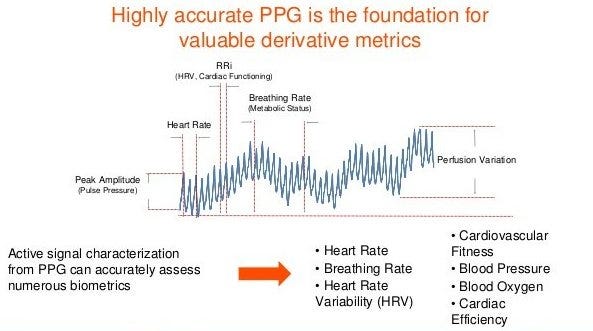

Medicine’s most iconic act, listening to your heart, offers one example of how inadequate the status quo (the stethoscope) is versus what’s already a few years behind the cutting edge (a $100 Fitbit.) Sampling a patient’s heart rate briefly once yearly, a doctor glimpses just 0.000016% of the period covered by a Fitbit, which checks and records the wearer’s heart rate every couple of seconds. That’s a black-and-white snapshot versus a movie capturing both minute-to-minute motion and longer term trends… what was your average heart rate last week or last month or last year? And it records micro-fluctuations in heart rate as the wearer breathes in and out — heart-rate-variability — a measurement that correlates strongly with both happiness and longevity.

But, at present, the average doctor doesn’t ask her patient for Fitbit data because, as several docs told an NPR reporter, they wouldn’t know what to do with it. One rationalized: “I get information from watching people’s body language, tics and tone of voice. Subtleties you just can’t get from a Fitbit or some kind of health app.” (Ironically, that’s exactly how doctors responded to early thermometers.) Some doctors actively avoid seeing the data, fearing that missing a subtle clue (perhaps discernible in hindsight after a heart failure) might trigger a malpractice claim.

Summing up, the industry is overwhelmed, defensive, recalcitrant.

Even when not swamped by innovation, the medical industry requires an average of 17 years to adopt significant innovations. How long is 17 years when measured against technology life cycles? By the year 2036, when the medical industry fully adopts 2019’s state of the art in technology — say asking every patient for her/his iWatch data dump — health technology will be at least 10,000-fold more sophisticated than today. In effect, the medical industry is a pogo stick chasing a star ship.

Read next: Part 7: Like fax machines, newspapers and encyclopedias, is medicine another information processing machine on the verge of being disintermediated by mutating consumer demands and tech innovation?

INDEX

Prologue: Two times Fitbit didn’t save my life; my six month journey on the borderlands of my own health data.

Part 1: My night continues downhill. Fitbit’s muteness gets louder.

Part 2: 23andme detects no clotting genes; demand for genetic expertise outpaces supply; DNA surprises about my personality and eating habits.

Part 3: A cartoon of the future of the medical industry.

Part 4: Five categories of predictable exponential tech change: devices, granularity, volume, utilization, software.

Part 5: Two categories of unpredictable change: the demands of individuals and their communities.

Part 6: Medicine, already trailing state-of-the-art techniques and technology by 17 years, gets lapped.

Part 7: Like fax machines, newspapers and encyclopedias, is medicine another information processing machine on the verge of being disintermediated by mutating consumer demands and tech innovation?

Part 8: Ten possible frontiers of consumer-led healthcare change.